Patty was walking to her office as she saw Professor Ulf Gabrielson pass by. "What an impressive older gent, " she thought. He had been a contender for a Nobel Prize a few decades ago and still came into the office most days. He was spry 85 years old, or so.

One thing about being in academia that struck Patty was the almost reverence for older professors. A handful of profs older than 70 taught and researched full-time, and undergrad and grad students eagerly sought their advice on technical, career, and, often, even personal matters.

The entire experience at Ivy U was working out well for her and Rob. They were both being awarded their PhDs soon. Now Patty wouldn’t feel so uncomfortable being a Prof without a PhD. Rob was getting a job as a Research Scientist at Ivy U after graduation. Although the position paid less than he could make in industry, he, too, liked the academic ambiance and flexible work schedule.

After walking into her office, Patty sat down to answer her emails and saw one from Mike Madigan.

It read, “Professor Coleman, could you and the team develop a list of recommendations on assembling mixed lead-free and tin-lead solders? Your humble student Mike.”

It was the break period between terms and Patty had some time; and this assignment sounded like fun. She immediately sent a note to Rob and Pete and suggested they all do some research then get together in a few days.

As always, the days passed quickly. "The team"was in Patty’s office in what seemed like no time at all.

“Hey, Rob! Now that you are a research scientist, do you get a better office than Patty?” Pete teased.

“Yeah, right! I’m now more famous than the world renowned Professor Coleman,” Rob shot back.

“OK! OK! Let’s get to work,” Patty said, chuckling along with Rob and Pete.

“What strikes me the most, in gathering information for this little assignment, is that, with all of the concern about the reliability of lead-free solder, so many people have assembled products with mixed technology and seem so cavalier about it,” Pete offered, seriously.

“I agree,” said Rob.

“Think about what a mixed solder alloy system this is. Four metals (tin, lead, copper and silver) in uncontrolled amounts throughout the solder joint,”Pete went on.

“So, you can’t really say what the melting temperature or mechanical properties are. They will vary throughout the solder joint,” Patty added.

“That’s all true, but we have to be a little practical. Many people have assembled with such mixed alloy systems with success – for a long time now,” Pete suggested.

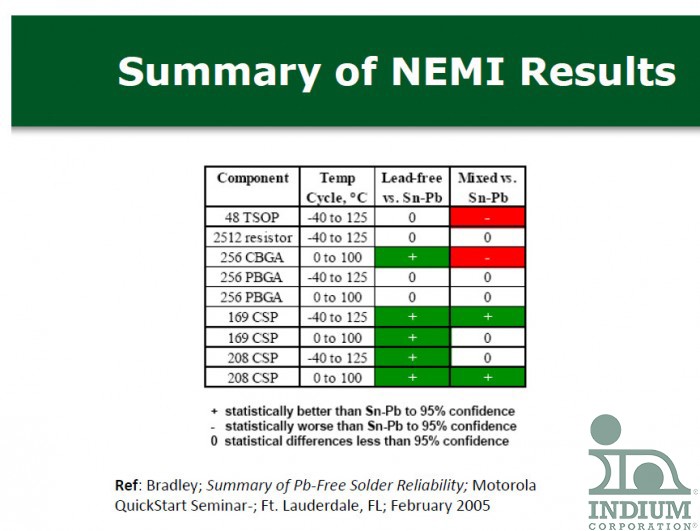

“Look at this work by Bradley et al with NEMI on thermal cycling,” Pete continued.

The trio looked at achart that Pete had printed out.

Figure 1.Bradley's data suggests thatmixed tin-lead and lead-freethermal cycle reliability is about equal to tin-lead solder reliability.

“Well, as expected, tin-lead solder is the laggard compared to lead-free solder. But, it is interesting that the mixed and tin-lead results are about the same.” Patty pointed out.

“The data show the typical situation. SAC solders are better in thermal cycle. If we had drop-shock data, the tin-lead and mixed soldermight look better,” Rob said.

The trio reviewed some other data for a short time…

“I think we agree that, for non-mission-critical electronics, mixed alloy systems can work. But, I think we also agree that, for something like a fighter jet or medical device, it shouldn’t even be considered,” Patty stated.

Rob and Pete murmured agreement.

“OK. So, it looks like these data support mixing tin-lead and lead-free solders. But, what about the process?” Patty asked.

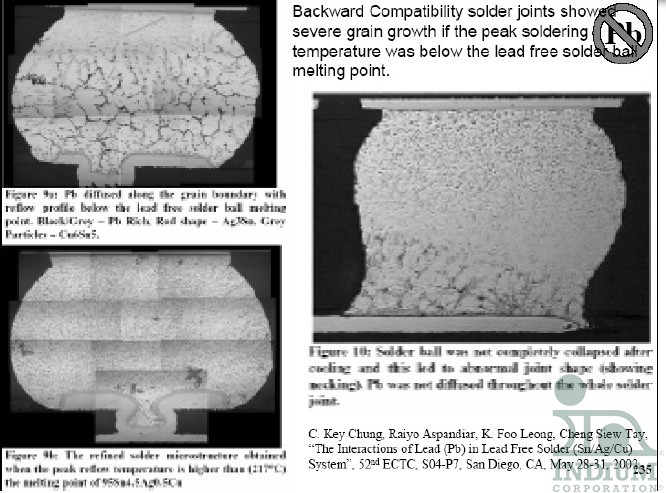

“We can’t use tin-lead soldering temperatures when also using SAC solder as we might not completely melt the SAC solder. Look at these images I found (see figure 2),” Rob said.

Figure 2. When using mixed tin-lead and lead-free solders, assure that the reflow temperature is high enough to melt the lead-free solder.

“Whoa!” Pete said. “Look at the poor grain structure! You don’t need to be a metallurgical genius to see that this solder jointis weak.”

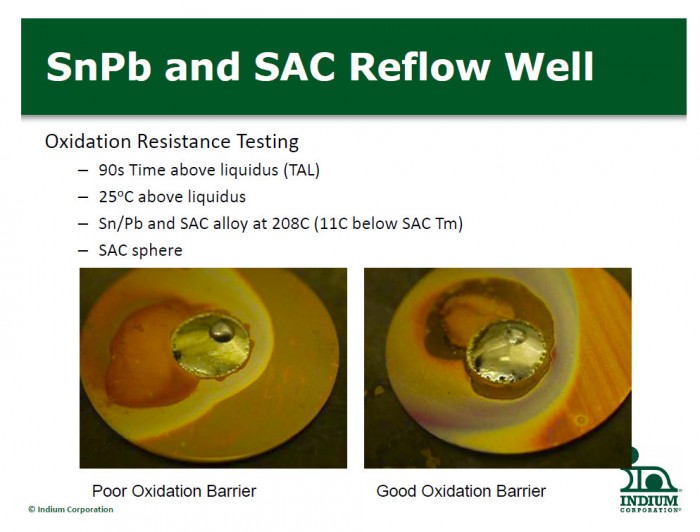

“I agree. But, if you are on the low side, temperature-wise, it really helps to have a solder paste that has a good flux. Remember the work that Mario Scalzo did relating to this? I have the photo of his experiment (see figure 3),” Patty said.

Figure 3. Although advisable to have the peak reflow temperature higher than the melting point of the lead-free solder (typically 219C or so), a good flux can aid in the melting of the lead-free solder at lower temperatures. The result, on the right, is at 208C.

I remember that work. He presented it at a workshop I attended. He was able to get a SAC305 solder ball to melt in tin-lead solder at only 208C. He used a terrific flux that aided the process,” Rob added.

“As we’ve seen before, a good solder paste is the place to start,” Pete added.

Patty went to her white board to summarize. She wrote down:

- Mixed lead-free and tin-lead electronics assembly can work for non-mission-critical applications.

- There should always be some discomfort as a four metal alloy system of varying composition is created.

- The resulting solder joint will have varying mechanical properties and melting temperatures

- Expect poorer thermal cycle results than SAC solders

- Drop-shock may be better than SAC solders

- The reflow profile should be such that the peak temperature is higher than the melting point of the SAC solder.

- As always, work with your solder paste supplier to obtain the best solder paste for this challenging application.

After they all reviewed the list and pronounced it sound, Pete suggested that they all play nine holes of golf.

Cheers,

Dr. Ron