Individually, indium and gallium each have some pretty interesting characteristics.

Gallium is liquid at 30°C (86°F) and, because it is less toxic than mercury and has a lower vapor pressure at higher temperatures, it is used as a mercury replacement in thermometers and other applications.

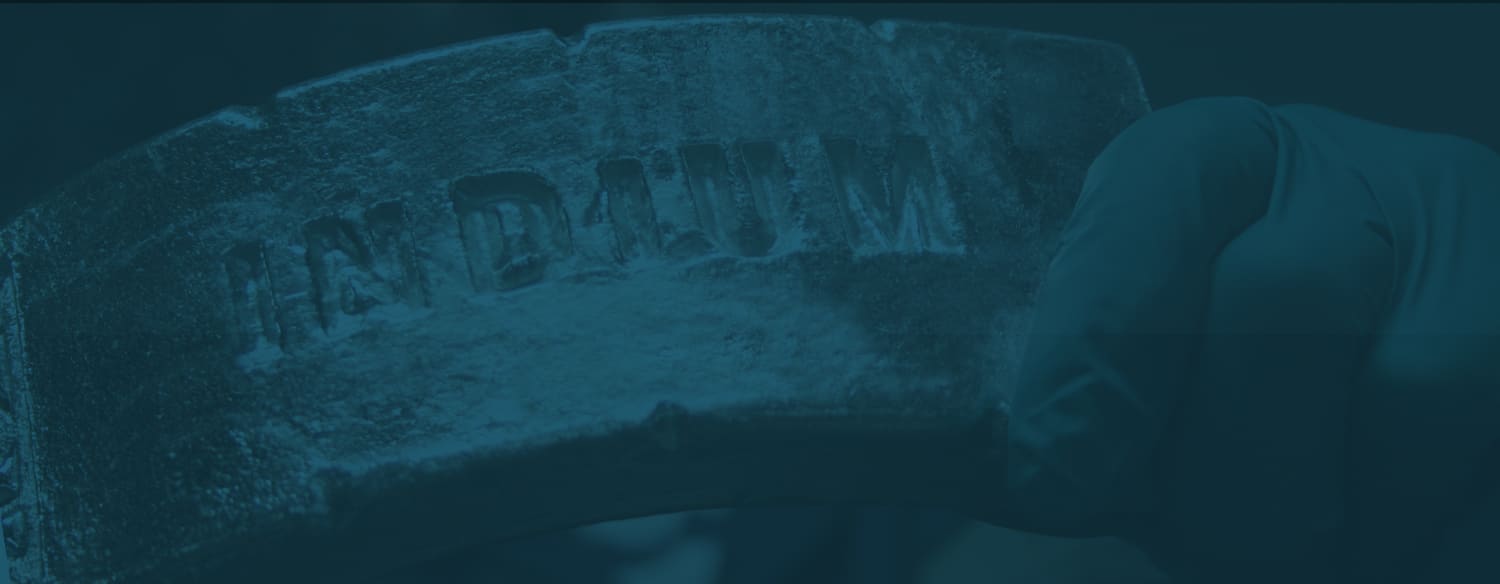

Indium, as I have discussed in previous blogs, has many unique characteristics including high thermal and electrical conductivity, resistance to thermal fatigue and reduced scavenging of gold in soldering.

But, combine the two, add a little tin, and the resulting alloys are liquid at, and below, room temperature (8°C to 25°C) and are very effective in conducting or dissipating heat away from temperature sensitive components. They can also conduct heat and/or electricity between metallic and non-metallic surfaces.

A recent study published by researchers at the McCormick School of Engineering, working with scientists around the world, discusses the use of an indium-gallium based alloy (EGaIn) to make stretchable electronics. The indium-gallium content overcomes the loss of conductivity that occurs when the material is stretched. The liquid alloy allows the "electricity to flow consistently even when the material is excessively stretched".

In 2009, researchers at the North Carolina State University used InGa to form antennae that would not break. Again it is the flexibility and the electrical conductivity of the liquid alloy that make this work. Michael Dickey and Gianluca Lazzi who headed the research, indicated they "were surprised" that the alloy operated at about 90% efficiency, similar to the efficiency of copper.

So whether on their own or combined, indium and gallium can be the solution to a variety of electronic challenges faced today. The Possibilities Are Endless!