Traveling in Malaysia recently, I met up with an old friend (and customer). We got talking about “lifetime” of solder paste: how long could the material survive various process steps before it became ineffective. Although we were both speaking good English (at least he was), there was a problem with technical communication that could have happened in any language; anywhere in the world. He and I were using the expression “staging life” to mean different things, and although the intent is not to tell anyone the right way to describe their process, I hope this provides some framework for discussions and helps us, in the industry, define our vocabulary.

"Materials" includes solder pastes, fluxes, epoxies, and others whose physical and chemical properties may change as a result of the extent of exposure to both higher temperature and to the ambient atmosphere, as the material progresses from storage to final use in its intended application. As an example, consider a dispensing, syringe-packed solder paste (although it could apply to almost any other fluid material used in electronics assembly and packaging). The process flow at the user site is:

1/ Solder paste is received in the overpack and placed in appropriate cold storage.

2/ Solder paste is removed from cold storage when needed.

3/ The paste is kept sealed in its syringes and allowed to warm to room temperature (usually a minimum of 4 hours).

4/ The syringe is uncapped (at both the top (end cap) and bottom (tip-cap)) and placed in the dispense machine and the solder paste is dispensed onto a substrate.

5/ There may then be a period where the paste deposit sits for a time before die or component placement on top.

6/ After the die or component is placed, there may be another period of time allowed before the final reflow process

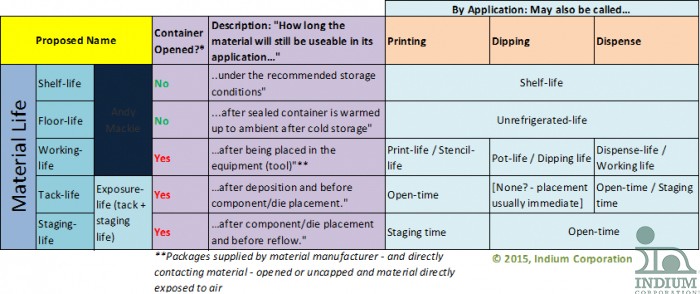

We’ve developed this table to describe the terms, as Indium Corporation sees them. You can expect the Indium Corporation tech team to use the same phrases in the same way:

To sum up the more complex parts:

Shelf Life: If the material is still in the container that it was supplied in, and has remained sealed under the supplier-recommended storage conditions, this period of time is the “shelf life”. Shelf life is usually determined by storing the material at different temperatures, from freezer to high ambient, then measuring the point at which one of the critical paste parameters goes beyond an allowable limit. Note that the properties are usually measured using a standard Quality Assurance metric for the paste: probably a series of standard IPC J-STD-005 and J-STD-004 tests such as tack, viscosity, or solderballing. However, most engineers realize that these tests often have little association with the way the material is used in a real process.

Working Life: We often have discussions with customers about how long a material will last once it is put into use: printing, dispensing, jetting, and so on. Working life is also referred to as “pot life”, although other terms, such as “open time” are used. In this moment, the material is now susceptible to loss of solvent and the effects of interacting with the atmosphere. Note that, although there is a lot of material here, and the surface area/volume ratio is low, the material is exposed to the air in a variety of degrees, depending on how it is used and packaged: dipping flip-chip flux will have a lot of exposure - syringe-packed epoxy much less so.

Tack-Life: Once the material has been deposited, it is now in a form where the surface area to volume ratio is at its highest. Therefore, it is most susceptible to effects from the atmosphere (moisture absorption, oxidation, and so on), and also to evaporation of solvent(s) from the flux. The effects of temperature will also be exacerbated. This time is necessarly kept as short as possible.

As you can imagine, the effects from each of these times will be cumulative, and a paste near the end of its shelf-life will potentially have a shorter working life and staging time.

I hope this helps clarify things a little and allows us to talk the same technical language.

Cheers!

Andy