In my last post, I talked about the advancements of medical technologies over the past century that have contributed to improving our quality of life, raising our life expectancy, and preventing previously debilitating diseases. There are three main application segments for medical devices (wearable, implantable, and industrial) and all of these devices work together in the medical field to diagnose, treat, and even cure illnesses. While most of us would be able to quickly identify a medical device, not many would see past the rigid outer assembly and understand what’s inside that makes it work. As a refresher, once the outer assembly is removed, the ‘brain’ of the device is exposed, which generally contains a battery, circuit board, and solder. So what type of solder is used inside medical devices? Well, that depends! Let’s talk about two types of wearable medical devices, hearing aids, and continuous glucose monitoring devices, as the applicable solder that’s used in each is generally the same.

Hearing aids were first commercially manufactured in 1913, although bulky and not very transportable. As with electronics in general, over the years they became smaller, stronger, and longer-lasting. In addition, there are many types of hearing aids available today, including in-the-ear, behind-the-ear, in-the-canal, etc. Hearing aids work by turning speech into an electrical or digital signal and then amplifying it through a microprocessor, where it is then converted back into a now louder sound through a speaker which the wearer can detect. While hearing aids have come a long way since their early beginning, the principle behind how they work and sound amplification has remained the same.

For slightly more than 100 years, the only way for diabetics to monitor their glucose levels was by pricking their finger to get a blood sample, which was then calculated by a glucometer. Today, however, many diabetics choose to wear continuous glucose monitoring devices (CGMs), which have been a revelation in providing insights and helping to track and manage diabetes. A CGM works by inserting a tiny sensor under the skin that measures the glucose found in the fluid in-between cells. The sensor measures the glucose every few minutes and transmits the information to a receiver through radio waves like Bluetooth. Unlike the ‘old-fashioned’ fingerstick method, which provides a single glucose reading, CGMs provide continuous, dynamic glucose level information – up to 288 readings in one day!

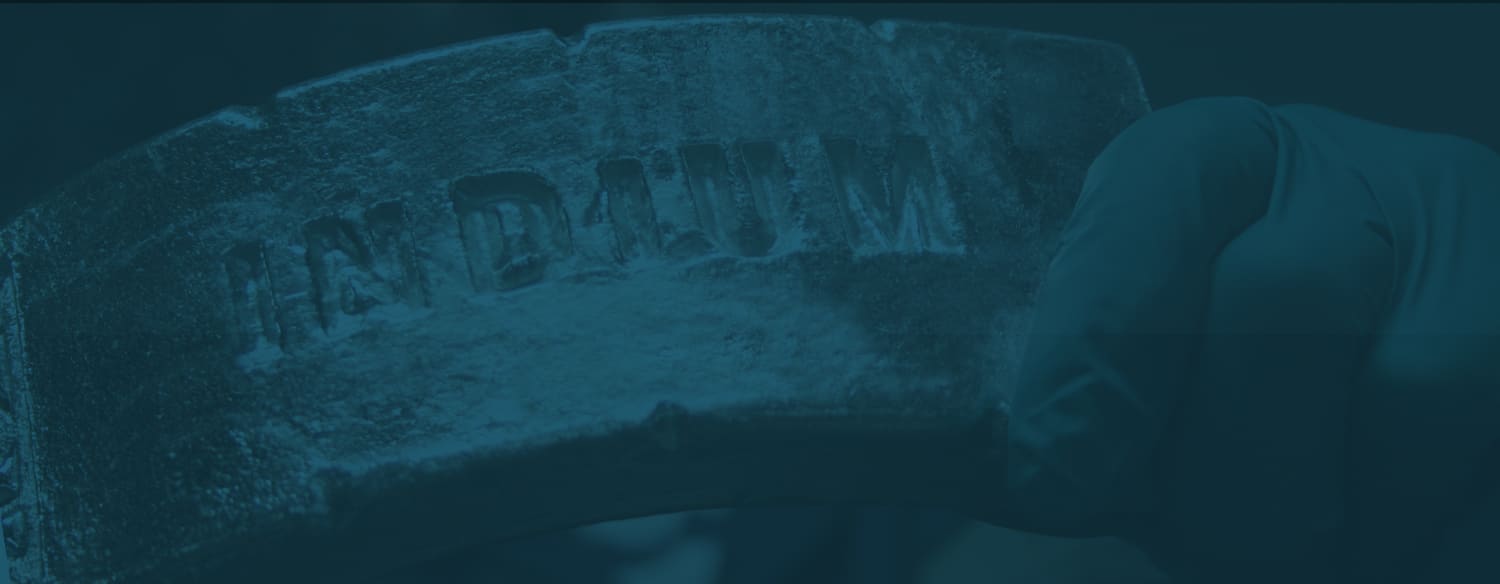

The solder material that is used in both of these devices is usually consistent. Both hearing aids and CGMs generally use fine powdered SAC305 solder paste, or equivalent, in the assembly. This complies with the needs of the manufacturing process of the device, but also with many environmental and health agencies around the world by being lead-free. In addition, while in some cases a water-washable flux could be used, the excellent electrical reliability of Indium8.9HF, a no-clean flux, provides the consistent high performance needed for medical applications.

In my next post, I will talk about implantable medical devices!